Misc

Colloquia

“Quaternions and Number Systems”

Rob Stephens, visiting professor here

Thursday, April 13, 2:45 PM, Newton 203

“Precision Medicine in the Age of ‘Big Data’: Leveraging Machine Learning and Genomics for Drug Discoveries”

Katie Gayvert, Geneseo math alumna, class of 2012.

Monday, April 17, 2:30, Newton 203.

Extra credit for write-ups of either or both colloquiua, as usual.

Problem Set 10 Solutions

PDF and LaTeX versions are available now in Canvas.

Questions?

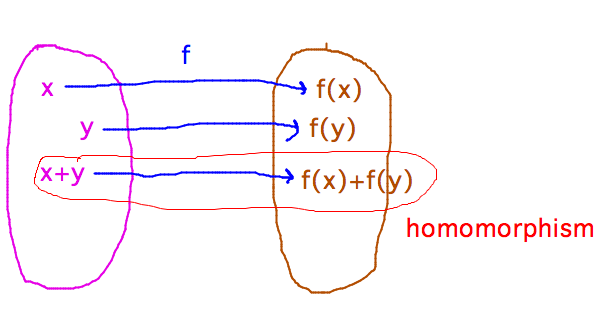

What is a homomorphism, as in question 5 of problem set 11?

- Think of combining arguments to and results from a function, as with addition or some similar operation.

- A homomorphism is a function for which it doesn’t matter whether you first do the combination to the arguments and then call the function, or first call the function and then combine the results.

Function Inverses

Section 6.5.

Basic Idea

Suppose A = { 1, 2, 3, 4 }, B = { 0, 1, 2, 3 }. Define f : A → B by f(n) = n (mod 3), and define g : A → B by g(n) = n - 1.

- n (mod 3) means the remainder after division by 3, as guaranteed by the division algorithm, i.e., the r in “n = 3q + r and 0 ≤ r < 3.”

Describe f-1 and g-1, in so far as either exists.

Relevant ideas or questions from the reading:

- Definition of inverse: let f : A → B, then f-1 is the set of ordered pairs { (b,a) | f(a) = b }, or equivalently the set of ordered pairs { (b,a) | (a,b) is in f }

Solutions:

- f-1 : B → A, and f-1 = { (1,1), (1,4), (2,2), (0,3) } since f = { (1,1), (2,2), (3,0), (4,1) }

- Because f-1 isn’t a function, the set of ordered pairs, or possibly an arrow diagram, is a better way to describe it than an equation would be.

- g-1(m) = m + 1

- This is a function, and lends itself well to being described by an equation

Comments:

- The most important thing this discussion exercised is the definition of “inverse” and some concrete examples of inverses.

- There are many ways to describe inverse functions, e.g., equations, sets of ordered pairs, arrow diagrams.

- Every function has an inverse (i.e., the inverse always exists, the “in so far as either exists” phrase in the directions for this discussion was a red herring), but it isn’t necessarily a function.

Theorems and Proofs

Suppose f : A → B is a bijection. Then you know that f-1 : B → A is a function. Is f-1 also a bijection? Is it even true that (f-1)-1 = f?

Solution (to one of the questions):

- It seems intuitive that (f-1)-1 = f.

- Proof: show that (a,b) is in (f-1)-1 if and only if (a,b) is in f. (a,b) is in (f-1)-1 if and only if (b,a) is in f-1, which is true if and only if (a,b) is in f. Thus (a,b) is in (f-1)-1 if and only if (a,b) is in f, and so the two sets, and thus the functions they represent, are equal.

Comments: This illustrates the common tactic of proving something about a function and its inverse by using the set-of-ordered-pairs definition of functions to infer things about a function from known facts about its inverse or vice versa.

Overall Comments

The most important ideas from today are understanding what a function’s inverse is, and being able to prove things about functions and their inverses.

You also saw a key requirement for f-1 to be a function, namely that f is a bijection.

Next

Images and inverse images of sets.

Read textbook section 6.6.